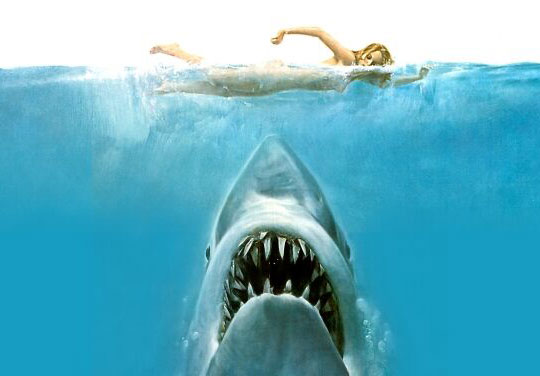

Whether it is that heart-stopping “du dut, du dut, du dut du dut du dut du dut in “Jaws” that tells you the shark is approaching, or the sweeping grandeur that underscores the first look at the Arabian desert in “Lawrence of Arabia,” or the sadly menacing trumpet solo at the beginning of “The Godfather” which foretells the violence and tragedy to come, the score of a movie is essential to the overall impact of the film.

It is why so many of us only have to listen to a brief portion of the score for memories of the film itself to come rushing back. In the paragraphs that follow I will list some of my favorite scores, and the reasons why they stick out in my memory out of all the many film scores I have heard.

This was a daunting task, in some ways even more difficult than picking out my favorite movies. There are so many wonderful scores to choose from, even from movies that wouldn’t necessarily be in contention for my favorite films. How do you choose between them? Do I include only original scores, or do I include adapted scores? Should I include musicals? Some scores stand alone as beautiful pieces of music, almost as if they were classical symphonies (“Schindler’s List,” “Out of Africa,” “Sophie’s Choice”), and some others are intrinsic to the film itself (“Jaws,” “Psycho”).

In all honesty, I could have scrambled any of my top 25 below and been just as happy with the order.

My first decision was to eliminate all movie musicals from consideration. I am planning on doing a future article on my favorite movie musicals, and so will review them at that point. My methodology for this intimidating task was to start with a baseline — the American Film Institute’s listing of the 250 greatest movie scores ever written. I then looked at all of the Oscar nominees for best original and adapted score to see if there were any movies that the AFI left off that I felt needed to be included. I then listened to a portion of the scores for all of these films and narrowed it down to 83 movies. Then, I scoured my list again to pick out only those movie scores I felt were either iconic or that I felt had a realistic chance at landing in my top 10.

This was excruciating. How to leave off “The Bridge Over the River Kwai” with its whistled “Colonel Bogey March” or the beautiful, wistful music from “Ragtime?” What about the inspirational opening theme from “Chariots of Fire” or the five-note communication with alien visitors in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind?” How about the jaunty “The Great Escape” or the chill-inducing “Tubular Bells” from “The Exorcist?” And don’t get me started on “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darlin’” from “High Noon!” Getting down to 34 film scores from which to pick my top 25 was almost like picking between children.

Without further ado, my 25 favorite film scores are:

1. “Vertigo” (1958), Bernard Herrmann — For those who have never seen “Vertigo,” one of the great all-time films, let me lay out the basic plot points without giving too much away. Scotty (James Stewart) is a retired police detective who after a tragic rooftop chase, has acquired a debilitating case of vertigo. He is hired by an old college acquaintance to follow the man’s wife Madelaine (Kim Novak) who he is concerned has mental issues and may be dangerous to herself. Scotty follows Madelaine and slowly begins to fall in love with her. This love will evolve into an obsession. The opening theme is portentous, off-kilter, lending the film a feel of mystery and dread. Then, as the credits end the action moves to the first scene of the film, the rooftop chase that ends with Scotty hanging by his fingertips from a great height, the music in this section intensifies into an urgent swelling of strings that propels the film forward, while establishing the harrowing theme that would underline the action each momentous time Scotty would be confronted with his vertigo. The music during Scotty’s nightmare is appropriately weird and jarring. But the highlight is the Scene D’amour, the music played during the penultimate scene when Scotty’s obsession reaches full flower. Note how the music reaches its zenith as Novak emerges from the bathroom and Stewart sees her remade for the first time. This is a perfect combination of performance, direction, cinematography and music. The music is lushly romantic and hauntingly beautiful, as you the viewer know that this obsession, and the treachery that underlies it, have reached the point of no return. This score is a masterpiece.

2. “Ben-Hur” (1959), Miklos Rozsa — A magnificent score by Rozsa, who seemed to specialize in scoring for large-scale epics. What is so striking to me about Rozsa’s score is the sheer number of different themes, all incredible, that he scatters throughout the film. There is of course the main title sequence. Then there is the ethereal, spiritual theme for every appearance of Jesus. The propulsive score he wrote for the Roman galley scenes, which underlies the physical and brutal treatment of the slave oarsmen in the underbelly of the Roman fleet; you listen to the music and the words “ramming speed” come flooding back to you. And, of course, the magnificent Parade of the Charioteers that plays as the chariots line up for what is simply the greatest action sequence in all of movie history — the chariot race. Finally, the ending miracle that is so heartrendingly beautiful, under-scored to maximum effect by Rozsa.

3. “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962), Maurice Jarre — In one of the most iconic film scenes of all time, Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) blows out a match and the shot cuts away to a sliver of sun beginning to rise over the Arabian desert. The music begins as a few anticipatory notes that swell as the sun takes form, and then culminates in the glorious main theme as the panoramic desert is laid out before you. It is as thrilling a movie moment as has ever been filmed and would not have had the same impact without the epic grandeur of Jarre’s theme, which is repeated throughout the film.

4. “Psycho” (1960), Bernard Herrmann — I don’t think anyone would ever call Herrmann’s score for “Psycho” beautiful, but Herrmann was a master at writing a score for a film that fit perfectly. Simply put, there would be no “Psycho” that we know and love today without Herrmann’s score. Listen to the score for the shower scene, and then imagine that scene without those shrieking strings and ominous bass notes. Pure genius.

5. “Schindler’s List” (1993), John Williams — Haunting, mournful and strangely comforting, much like the film itself. I own this soundtrack on CD, and play it often when I want to listen to something absolutely and completely beautiful.

6. “The Godfather” (1972), Nino Rota — From the first notes of that menacing, sorrowful horn, you instinctively know that what you are about to see will be tragic and violent. That Rota is able to combine that rich main title with the gorgeous love theme is astounding. Then add in the theme that corresponds to Michael’s ascension to Godfather, and how it punctuates the profound sadness of a man’s fall from grace. Bravissimo!

7. “Rocky” (1976), Bill Conti — Certainly the most inspiring film music ever written. Robust, compelling and thrilling, it is practically an anthem to individual desire and dedication.

8. “Out of Africa” (1985), John Barry — Another score that I love to listen to just for the sheer beauty of it. The main title is amazing, and the music for the scene where Denys (Robert Redford) takes Karen (Meryl Streep) up in a plane over the African savanna is breathtaking.

9. “Jaws” (1975), John Williams — Like “Psycho,” the music to “Jaws” is never going to win any beauty prizes, but it is intrinsically essential to the success of the film. I wonder how many people in daily life hum the theme from “Jaws” in both serious and comical situations. Those ominous, repeating notes that are practically a musical substitute for a shark’s fin are arguably the most famous individual notes in film history. The rest of the score is pretty darn good too, perfectly suited to an adventure movie (which “Jaws” really is, more than horror).

10. “Laura” (1944), David Raksin — “Laura” is an acknowledged film noir classic, but it really is not a movie that should have worked as well as it does because certain aspects of the plot really strain the bounds of credulity. It is the central conceit, of a detective who falls in love with the murder victim, that distinguishes the film, but that conceit would not have had its spellbinding impact if not for the score by David Raksin. It is a score that is at once romantic and hypnotic, and is incredibly effective in making the viewer believe in the detective’s obsession. When asked why she turned down the lead in the movie, Hedy Lamarr was quoted as saying, “They sent me the script, not the score.” What more is there to say?

11. “Gone With The Wind” (1939), Max Steiner — A grand score, that totally matches the scale of the film itself. People often think of “Gone With The Wind” as a Civil War film first, but it really is at heart a romantic melodrama, and Steiner’s score bridges the gap between the melodrama and the historical scope.

12. “Sophie’s Choice” (1982), Marvin Hamlisch — “Sophie’s Choice” is arguably the most profoundly sad movie ever made. I certainly will never forget the first time I saw it and how it affected me. I also will never forget Hamlisch’s poignant love theme, one of if not the most beautiful movie themes ever written. Sometimes, though, the best decision is to have no score, and in the choice scene, and anyone who has seen the movie knows exactly which scene I am referring to, director Alan J. Pakula wisely chose to not have any score, just the ambient noise of the surroundings. The combination of the silence of that scene, with that hauntingly beautiful score that underpins everything before and after it, helped to make this one of my most indelible film experiences.

13. “Patton” (1970), Jerry Goldsmith — The blare of trumpets that begins “Patton” (after, of course, that electrifying, one-of-a-kind speech that opens the film) gives a hint to the mystical element to Patton’s personality, and his belief that he was reincarnated. Then the score proceeds into a rollicking marching tune, a propulsive, driving theme that correlates to Patton’s hard-charging personality. It is a perfect complement to this incredible biography of the charismatic World War II general, and this unabashedly pro-war film released in an anti-war era.

14. “The Sting” (1973), Marvin Hamlisch — Okay, maybe this is a bit of a cheat, but it’s my list so what the hey. This is an adapted song score, and not an original score. In fact, there is very little original music in the film, most of it adaptations of rags written by Scott Joplin, most notably “The Entertainer.” But the jaunty music is so apropos to the mood of the film that it practically fits like a glove.

15. “Love Story” (1970), Francis Lai — Yes, the story is treacly and Ali MacGraw can’t act worth a darn. But the film was a huge hit, and I truly think most of the credit for that goes to Francis Lai’s score. Much like “Laura,” the film is elevated by the score above and beyond the limits of its screenplay.

16. “Wuthering Heights” (1939), Alfred Newman — The ultimate gothic romantic tragedy receives the appropriate treatment in Alfred Newman’s very dramatic score. The strings in the main theme are practically dripping tears, and the romantic in me cannot resist a film that ends with the choir of angels.

17. “North by Northwest” (1959), Bernard Herrmann — Cary Grant plays a businessman who in a case of mistaken identity is believed to be a government agent by a spy played by James Mason, which leads to attempts on his life, a frame-up for a murder he didn’t commit, a flirtatious affair with a mysterious woman played by Eva Marie Saint, and a final confrontation on top of Mount Rushmore. Herrmann’s score moves seamlessly from dissonant sounds that plays up the businessman’s sense of displacement, to exhilarating passages that propel the action forward, to an enchanting refrain for the two lovers and finally a percussion-laden finale that drives up the suspense.

18. “The Magnificent Seven” (1960), Elmer Bernstein — You may not realize it, but listen to just a few seconds of the theme song from “The Magnificent Seven,” and you will hear just how familiar it is. It is perfectly suited to this tale of seven gunmen who come to the rescue of a small Mexican town terrorized by outlaws. Listening to it, you can practically see the horse rails and tumbleweeds, and feel the excitement.

19. “Casablanca” (1942), Max Steiner — There is one song that is synonymous with “Casablanca” — “As Time Goes By” — and it features prominently in Steiner’s score. However, the score is not just a rehashing of the song. Steiner brilliantly adapts the song and merges it into his own arrangements with original music that both emphasizes the doomed romantic aspect of the story yet marries it to the historical importance of the time and place.

20. “The Adventures of Robin Hood” (1938), Erich Wolfgang Korngold — Considered one of the founders of modern film music, along with Max Steiner and Alfred Newman, Erich Wolfgang Korngold began composing film scores in 1934 after emigrating from Austria where he had been an internationally renowned composer of symphonies but left to escape the Nazis. His total filmography is rather limited as his career as a film composer only ran from 1934 through the end of World War II. In 1939, he graced us with his triumphant score for the swashbuckling masterpiece “The Adventures of Robin Hood” starring the incomparable Errol Flynn. It perfectly matches the tone of the film itself — fun, lively and devil-may-care and yet at the same time rather ceremonial.

21. “The Mission” (1986), Ennio Morricone — “The Mission” is a film about Jesuit missionairies establishing a successful mission in the jungles of South America in present day Argentina that is threatened by political agreements between Spanish and Portuguese colonists, and a complicit Catholic Church. The score is heavily influenced by indigenous instruments native to the region where the film is set, which lends a feel of authenticity. Composer Ennio Morricone in his score tries to represent the conflicting cultural aspects — the Spanish colonists and the native peoples — to highly emotional impact. It is a gorgeous score that expertly complements the human disgrace the film depicts.

22. “Body Heat” (1981), John Barry — A movie about animal attraction, lust and greed, “Body Heat” is a great modern film noir about a torrid affair between the married Matty Walker (Kathleen Turner) and seedy lawyer Ned Racine (William Hurt) that turns to murder and betrayal. Sultry and mysterious, Barry’s jazzy score practically drips with humidity and sex.

23. “Star Wars” (1977), John Williams — I have probably alienated half the world’s population by putting John Williams’ iconic score for “Star Wars” this low on my list. Truth is, it’s a great score for a groundbreaking film and I wouldn’t argue with anyone who insists it should be higher. I simply didn’t have the heart to replace one of my other choices, most of which are for films which I love more than “Star Wars.” Listening to the score again brought me back to the first time I saw the film with that scrolling prologue and the spectacular sight of the spaceship seeming to float in space. The fanfare that begins the score appropriately seems to announce the dawning of a bold new era, as “Star Wars” did in the history of Hollywood movie-making.

24. “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981), John Williams — The ultimate popcorn movie. Williams’ score pinballs between a mystical ambiance, a sumptuous romanticism and, of course, that triumphant, brassy march.

25. “Dr. No” (1962), Monty Norman — This one really is a condundrum for me. John Barry wrote the score for 11 James Bond films before his death in 2011, and the scores he wrote for those films are generally considered the most accomplished in the series. However, the one thing John Barry did not write was the James Bond theme, that has been used in one form or another in every James Bond film produced by Eon Productions (only two Bond films were not produced by Eon — “Casino Royale” (1967) and “Never Say Never Again” (1983). The James Bond theme was written by Monty Norman for the first Eon-produced Bond film, “Dr. No” in 1962. That iconic theme song, which is generally used at the beginning of every film and again at the climax, is so recognizable to Bond fans and non-fans alike that it is practically indistinguishable from the character itself. Thus, my decision to credit Norman and “Dr. No,” even though this is not the finest score overall in the series.

Honorable mention:

“War Horse” (2011) – John Williams; “Glory” (1989) – James Horner; “Charade” (1963) – Henry Mancini; “Avalon” (1990) – Randy Newman; “Doctor Zhivago” (1965) – Maurice Jarre; “Now, Voyager” (1942) – Max Steiner; “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) – Howard Shore; “Chinatown” (1974) – Jerry Goldsmith; “The Pink Panther” (1964) – Henry Mancini

Also considered:

“An Affair to Remember” (1957) – Hugo Friedhofer; “Airport” (1970) – Alfred Newman; “Anatomy of a Murder” (1959) – Duke Ellington; “Around the World in Eighty Days” (1956) – Victor Young; “Born Free” (1966) – John Barry; “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961) – Henry Mancini; “The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957) – Malcolm Arnold; “Chariots of Fire” (1981) – Vangelis; “El Cid” (1961) – Miklos Rozsa; “City Lights” (1931) – Charles Chaplin; “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) – John Williams; “Empire of the Sun” (1987) – John Williams; “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” (1982) – John Williams; “Exodus” (1960) – Ernest Gold; “The Exorcist” (1973) – Jack Nitzsche; “Field of Dreams” (1989) – James Horner; “The Great Escape” (1963) – Elmer Bernstein; “The Greatest Story Ever Told” (1965) – Alfred Newman; “Halloween” (1978) – John Carpenter; “The High and the Mighty” (1954) – Dmitri Tiomkin; “Hign Noon” (1952) – Dimitri Tiomkin; “Hoosiers” (1986) – Jerry Goldsmith; “How Green Was My Valley” (1941) – Alfred Newman; “In the Heat of the Night” (1967) – Quincy Jones; “King Kong” (1933) – Max Steiner; “L.A. Confidential” (1997) – Jerry Goldsmith; “The Lion King” (1994) – Hans Zimmer; “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing” (1955) – Alfred Newman; “Murder on the Orient Express” (1974) – Richard Rodney Bennett; “The Natural” (1984) – Randy Newman; “The Omen” (1976) – Jerry Goldsmith; “On the Waterfront” (1954) – Leonard Bernstein; “Once Upon a Time in the West” (1968) – Ennio Morricone; “Papillon” (1973) – Jerry Goldsmith; “Ragtime” (1981) – Randy Newman; “Saving Private Ryan” (1998) – John Williams; “Shane” (1953) – Victor Young; “The Shawshank Redemption” (1994) – Thomas Newman; “The Song of Bernadette” (1943) – Alfred Newman; “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1951) – Alex North; “Summer of ’42” (1971) – Michel Legrand; “Superman” (1978) – John Williams; “The Ten Commandments” (1956) – Elmer Bernstein; “The Third Man” (1949) – Anton Karas; “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962) – Elmer Bernstein; “25th Hour” (2002) – Terence Blanchard; “The Untouchables” (1987) – Ennio Morricone; “Wait Until Dark” (1967) – Henry Mancini; “The Way We Were” (1973) – Marvin Hamlisch